The Settlement at The Farms: The Stone Fort and King Philip's War (part 2)

Lesser bridges figured prominently in the settlement of the wilderness, too. In 1665 George Fairbanks' daughter, Mary, married Joseph Daniell and settled with him just a mile or so away from her father, but on the other (south) side of Bogastow Brook. Benjamin and Martha Bullard’s closest neighbor, George Fairbanks was also Martha’s step-brother. George complained to the town that the cart-way over the brook was inadequate. A proper bridge was built over the brook, which allowed George to visit his daughter more conveniently and more families spread to the south side of Bogastow Brook, including a number of Benjamin Bullard’s children who eventually numbered eleven.

By the time the Bullard, Fairbanks, Leland, Clark and Daniell families built their homesteads at “the Farms” across the river from Medfield in the 1650’s, there had already been one “Indian War” in 1637. From the first settlement, when English towns were incorporated colonial law required a constant watch be maintained. The required signal for an attack, which varied slightly from town to town, was either the discharging of three muskets, a continuous drumbeat, lighting a signal beacon or firing a cannon. Garrison houses were built to shelter the town’s inhabitants in case of attack.

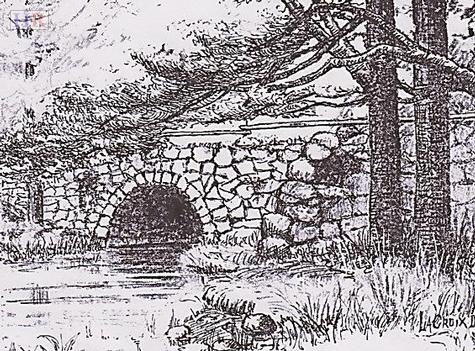

The Reverend Abner Morse wrote in The History of Sherborn, that the garrison house at the Farms was “a spacious and regular fortress. It was superior to any similar structure on the [then] frontier. It was 65 or 70 feet long, two stories high, all of faced stone, brought over ice from a quarry one mile distant ... and laid in a workmanlike manner in clay mortar...” Although it was built on George Fairbanks’s property, legend and (some say) archeological evidence has it that the stone house was supplied with water by gravity through an underground wooden pipe from a major natural spring at up the hill at Benjamin Bullard's neighboring farm. It is probable that the garrison house was kept amply stocked with provisions. The settlers sheltered inside would have been able to remain secure for many weeks, if necessary, without suffering from want of provisions or water.

In 1642, five years after the Pequot War the Narragansett sachem, Miantonomo told his people, “Our fathers had plenty of deer and skins. Our plains were full of deer as also our woods, and of turkeys, and our coves full of fish and fowl. But these English having gotten our land, they with scythes cut down the grass, and with axes fell the trees; their cows and horses eat the grass, and their hogs spoil our clam banks, and we shall be starved.”

John Elliot, a Puritan missionary born in Widford, Hertfordshire, England received a commission and funds from England's Long Parliament to settle the Massachusett Indians on both sides of the Charles River, on land deeded from the settlement at Dedham. In 1651, he established the Praying Indian town of Natick, Massachusetts. Eliot is best known for attempting to preserve the culture of the Native Americans by putting them in thirteen planned towns where they could continue to rule themselves, with Natick as the political and spiritual center. Of course, they were required to convert to Christianity and live like the English. Eliot and Praying Indian translators printed America's first Indian Bible and in so doing inadvertently preserved the Algonquian language.

From the first colonial settlement, the royal charter under which the Puritans operated required the settlers always to extinguish any Indian claims to the land they settled. In practice this was commonly done collectively by identifying all Indian sachems (as representing their peoples) who may have had a valid claim to the use of particular land, and negotiating with them (now quite familiar and practiced in dealing with the English) on mutually agreed fair terms for selling those rights. Failure by many of the settlers, including Benjamin Bullard (see later), to observe this obligation was part of what was making the Indians increasingly angry.

In 1671 rumors spread that Massasoit’s son and heir Metacom (also known as Philip) was arming himself and his people. He was summoned to the General Court where he was so accused. He was publicly humiliated by being forced to hand over his weapons and sign a confession of disloyalty. It became clear to Metacom that the English were intending to make the Indians their subjects instead of allies and partners on the land. By the 1670’s, many of the Massachusetts Indians who had survived the smallpox epidemics of 1628 and 1633, the Pequot War of 1637 and the pressure for conversion to Christianity in the 1650’s, were justifiably angry over the usurpation of what had been the land and customs of their ancestors. Metacom made the difficult choice to begin arming his people against the English.

In 1675 Metacom’s closest confidante betrayed him and traveled to Plimoth Colony to warn the English that the Indians were preparing for war. Three weeks later that messenger was found dead. The English arrested three of Metacom’s men, tried and executed them in defiance of a long standing agreement that Indian crimes would be punished by Indian law. The Indians justly felt that their sovereignty had finally been completely taken from them. Throughout the spring reports of the coming war continued to spread among the English.

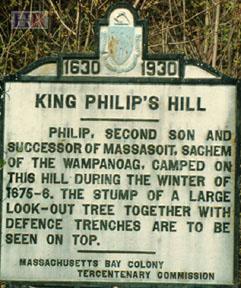

In June of 1675, Swansea was burned. Through the summer and fall the war spread and terror increased. Reports of battles at Hadley, Hatfield, Deerfield, and Springfield out in the Connecticut River Valley were speedily carried the eighty odd miles eastward. By the winter of 1676 to travel outside of Boston was a dangerous affair. The war spread to Connecticut and Rhode Island. Closer to home, Lancaster was attacked on February 10th, 1676*, and the outlying village of Mendon was then evacuated as being indefensible against the numbers of Indians commanded by sachem Metacom, son of the peaceful Massasoit, known by the English as King Philip. Medfield was warned to prepare and a number of militia men were sent there to defend it.

As the gathering animosity between English settlers and Indigenous Americans became increasingly obvious, the settlers looked to their safety. Scarcely six miles up the river from the town of Medfield and the settlement at the Farms, was the Praying Indian town of Natick. Although the families living there had, twenty years earlier, sworn allegiance to the English crown, cut their hair, given up Indian dress and customs, built houses and schools and prayed every Sunday in the church they built for John Eliot, in November 1675, the English settlers summarily gathered together the Indians of Natick and drove them on foot to the Charles River. There they were put into canoes and sent down to Boston Harbor where they, along with the inhabitants of the other Praying Indian towns, some six hundred men, women and children were deposited on Deer Island with no food, shelter or blankets on an island in Boston Harbor where predictably three to four hundred died during their internment.

The Indians led by Monoco, a chief who lived near Lancaster (according to Jameson), attacked Medfield village on February 21, 1676. According to William Hubbard “The western towns above Connecticut were the chief seat of the war, and felt most of the mischiefs thereof in the end of the year 1675/6,* but the Narragansett, having been driven out of the country fled through Nipnet Plantations towards Wachusett Hills, meeting with all the Indians that had harboured all winter in those woods about Nashaway…one half of them were observed to bend their course toward Plimoth taking Medfield in their way, which they endeavored to burn and spoil [on] February 21, 1675 as their fellows had done [at] Lancaster ten days before…”[Hubbard, William; A Narrative of the Indian Wars in New England; Brattleborough;1814].

* The discrepancy in dates (1675 vs. 1676) almost certainly comes from the double dating difference between the Julian and Gregorian calendars concerning when the year started.

The attack at Lancaster had sufficiently alarmed the neighboring villages and thanks to the New England Confederation several had requested and obtained garrison soldiers as was the case at Medfield, twenty two miles from Boston. The “surprisal” therefore, of Medfield, was in fact expected. Apparently, according to Hubbard, the soldiers were billeted throughout the town (a common practice and one of the more problematic issues for angry colonists a generation later) rather than in a central location and when the attack began, they were unable to gather quickly enough to save the town.

In fact, it was a brilliantly tactical move on the part of the Indians. At daybreak the warriors nearly simultaneously lit fires in all the standing structures and regardless of how many soldiers were there to defend them, the concurrent attack on the people fleeing the burning buildings resulted in utter chaos amongst the English and rendered them unable to protect themselves or their town. Most of the town had already been set alight before the cannon could be fired, which Hubbard says “frighted away” the “Cannibals” but plainly the Indians knew the cannon signal as well as the colonists did. When they had crossed over the bridge they set fire to that to “hinder our men from pursuing them”. Seventeen people were killed outright (one man’s wife shot herself after he was killed) and damage to the town amounted to more than two thousand pounds. Again, according to Hubbard, “James the Printer” left a “writing” or note near the burning bridge in Medfield. Written in English, it read as follows:

Know by this paper that the Indians that thou hast provoked to wrath and anger will war these twenty-one years, if you will. There are many Indians yet. We come three hundred at this time. You must consider that the Indians lose nothing but their lives; you must lose your fair houses and cattle.

According to Carmen Lopez, director of the Harvard University Indigenous American Program, no one knows exactly how many Indians attended Harvard during the Puritan period. The names of only six survive: John Sassamon; James Printer; Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, Joel Iacoombs, both Aquinnah Wampanoags, John Wampus, class of 1669, attended for a short period and then quit Harvard to go to sea as a mariner; and Eleazar, last name unknown, class of 1679, a Wampanoag. Joel Iacoombs was to have been Harvard valedictorian in 1665, but died in a shipwreck just before graduation. Instead, Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck wrote and delivered the traditional Latin oration at the Harvard graduation ceremonies of 1665.

After crossing and burning Death’s Bridge they camped for the night just a mile and quarter to the southeast, literally at the top of the next hill from the stone fort where the families at the Farms having seen the smoke and heard the cannon from across the river at Medfield had fled. During the cold February night that followed, Jameson says; “the red glare of the pow-wow fire was seen shining on the tall trees of the forest in the southern horizon, the fierce war-whoop of the savage in the dance of triumph might have been borne over the silent fields and added a new pang to the hearts already overburdened. Nothing but their trust in God could have sustained them in such an hour…”.

The spot where they rested is marked today as it was in 1676 by a curious clump of trees called Swamp Hornbeam or Umbrella Tree although the housing development now adjacent to the spot makes the trees hard to find. Indigenous Americans called it Inpelo; from this is derived its third common name, Tupelo. Its scientific name is Nyssa sylvatica. The trees are not particularly common to the area and there was at one time, a fair amount of speculation about the fiendish origins of that particular clump of Hornbeam.

The “King Philip Trees” - drawing from The History of Medway by Rev. E.O. Jameson.

According to Jameson “The savages, in the morning, still bent upon the work of destruction, pressed on towards the stronghold...The Stone House did not readily yield to the attack of the savages. Musket balls had little effect, and the keen fire of the defenders kept the assailants at a safe distance. How early the attack commenced, how long it continued, or how persistently it was pressed, there are no means of knowing. Nor do we hear anything of the killed and wounded. Probably the thick stone walls fully protected those within…”

The Indians returned in May but were frustrated in their attempt to burn the George Fairbanks garrison house by a providentially placed stone which stopped the burning cart full of hay or other combustible material sent down the hill towards it. They were frustrated in their attempts to move the cart off the rock due to the settlers firing at them from within the stone house. The stone house became a family icon and the ancestors who built and defended it were revered by their nineteenth century descendants for their grim courage and stoicism.

The war destroyed twenty five English towns and 2000 English were killed. The fortunes of war were favoring Philip/Metacom until the Mohawks allied with the English and attacked Philip’s men and killed 500. A year later scores of Indian villages had been burned, 5000 native people had died and those who survived were sold into slavery in the West Indies. Philip was killed in August, by a Praying Indian named John Alderman who along with an English Militia unit surprised what was left of his people. Philip’s head was displayed on a pole in Plimoth for twenty years afterwards and his son was sold into slavery in the West Indies.

The burning cart and the garrison house at the Farms, 1675 interpreted by George J. LaCroix. As described by Morse, the building was clearly much larger.

© Copyright 2012, Martha L. DeWolf

Martha, You have captured the spirit and the reality of those very hard times. Thanks for bringing Holliston history to life.

Paul | 2012-02-17 17:38:57